DOODSAKKER

To get to the abandoned city, you must first endure a more than 100 km-long route through the Namib Desert and reach the scarily-named town of Tiger Bay. Even the name Namib sounds scary, if we were to translate its meaning. It comes from the language of the Nama people, meaning “the place where there is nothing”. The oldest desert and the highest dunes in the world.

Satellite map showing the route. The blue path indicates the route through the desert; the red one the Doodsakker, known as the death zone; yellow indicates the route taken by boat.

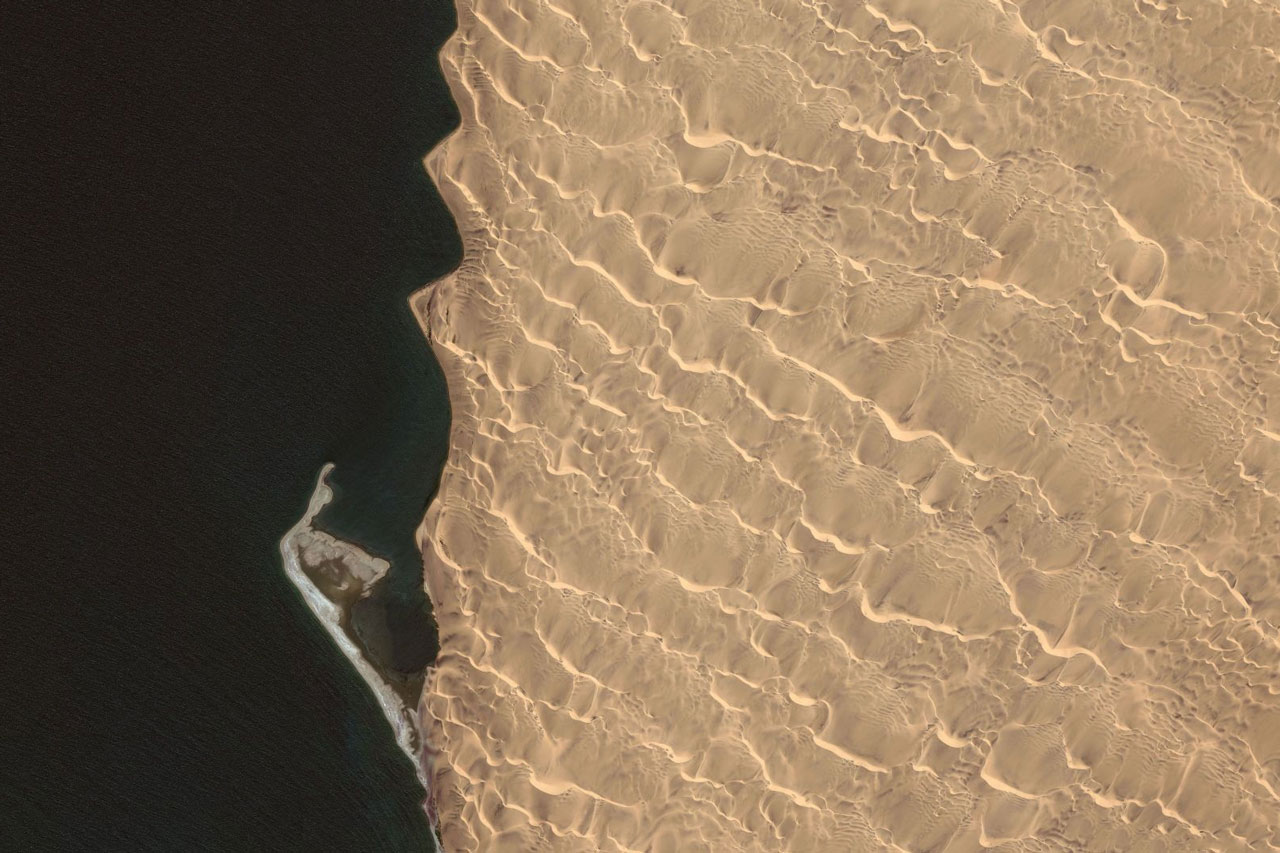

Satellite image – close-up showing part of the route through the Doodsakker as well as the desert with dunes.

Before we go into this inaccessible and lifeless area, we need a little practice (and at the same time see the surrounding wrecks) – to learn to recognise and avoid the dangers of the desert. There are salt swamp sinkholes, damp depressions covered with a thin, dry layer of sand or unusually fine sand that can, however, immobilise a vehicle. A fully-equipped vehicle with spare parts, extra fuel tanks, water and a mass of different types of equipment like a 4-tonne truck. Driving it through the desert is a completely new experience.

On 23 November, we are ready. The date is not accidental. But more about that later.

Thanks to a chance meeting and the help of our Russian colleagues, geologists (and with knowledge of Russian, of course) searching for oil, we obtained a detailed geological map of the desert. It helped us get oriented and overcome the first kilometres. At first, the road is marked with small wooden stakes embedded in the sand to show us the correct direction. Driving between them is supposed to be safer, as this area has been checked for the presence of mines. They are still present after the recently-ended civil war. “Mines in the desert?” I thought. “Impossible. Who would put them there? And, above all, against who or what if no reasonable person ever ventures into these areas.” But soon the road twists to the east and we must head south. All that remains is the blind faith that I’m right.

The further south we go, the more difficult the terrain becomes. The heavy truck can easily get stuck in the sand. Reducing the pressure on the tyres does not help. To defeat the boggy, sandy terrain we have two strategies. Drive slowly to give ourselves time to stop and safely reverse. Or drive faster and harder to defeat a stretch using the power of our momentum. Sometimes, however, the distance is too long or the sand is too slushy. The tyres cannot overcome the resistance of the fine sand or find enough support. Even speeding, with the reducer on and blocking the differential gear, it comes to a standstill after several dozen metres. The wheels immediately sink, taking the whole car with them.

Attempts to dig out or pull the car out from the trap only make the situation worse. The wheels are buried so deeply that the car is resting on its frame. Then even the sand ladders don’t help. Instead of the wheels, we have to dig out the entire car. After several of these events, we change tactics. When the truck stops under the pressure of the sand, we do not try to dig it out. We immediately put sand ladders under it and only then do we try to drive out. Overcoming this stretch is then much easier and faster. When one sand ladder comes out from under the wheels, we immediately put in a second one in order to extend the car’s movement and seamlessly get out of the fine sand.

I’m not worried by the blazing sun and the 40-degree heat. I’m not worried that the car is too heavy. I’m not even worried about digging out the car several times with shovels and wasting energy on the car. We reach perfection – one mound on the right, the second on the left. The loss of time worries me the most. Precious time. Each moment I peek at my watch. Stress starts to set in. Again and again we are buried and are running behind.

30 kilometres or so later, the first dunes begin. It’s best to move on their backs, where the sand substrate is much harder. You have to be vigilant all the time though. The monochromatic dunes merge into a single entity and it is hard to see where one ends and the other begins. You can’t go blindly. Driving recklessly can end with the car falling from a dune a few metres high. And the end of the trip. Soon, however, the dunes become so high and steep that we cannot continue to go up them. So we turn east and head towards the coast. Fortunately, it is not far.

Driving along the coast, we begin a second, more than 50 km stretch of road called the Doodsakker, which loosely translates to “the death zone”. On the map I am using only two words appear: “extremely dangerous”.

This place is one of two in the world where dunes a few dozen – and even a few hundred – metres high descend directly into the ocean. There is no beach known for its typical seaside resorts. That is why time is of the essence. Days and hours. It is only twice a month, during the new or full moon, that the tides are low enough to expose a small part of the beach that we can drive on.

The next low tide begins on 23 November at 9:53 and lasts about 3 hours. The difference in the water levels between the low and high tides is about 1.20 metres. This difference, plus the additional half metre of rough waves that can completely inundate and immobilise the vehicle. And that is where my stress comes from. You must reach the ocean and start the drive at exactly the right time. Once or twice again we are buried and we cannot keep the pace. Or, worse, high tide could come in during the crossing.

Everyone I talked to advised against passing through this area, especially in just one car. They said that the returning high tide can surprise people unaware of the danger. The rough waves can easily flip or immobilise vehicles. Salt water can flood the engine, the battery and destroy the vehicle’s electric wiring. Or adhere it to the floor. Then help can only come from a truck or crane. But where would they come from? I could barely believe such a story until I saw some pictures of a completely flooded car or its wheels protruding just above the water. It caught my imagination.

And so it is time for a real adventure and a real challenge. Challenging the data of nature.

Initially, the exposed strip of beach is very wide and the dunes are small. We quickly go along the shore marvelling at the view and frightening the unsuspecting seals basking on the beach. After 20 kilometres the dunes become ever higher and the beach narrower. In some places, it is so narrow that the car tilts and the right wheels wade in the water. The steep, high dunes do not allow us to ascend or cross them on their sides. You have to go by the narrow beach and sometimes in the water. This is the most dangerous stretch. Particularly that the fresh, dry sand blown from the dunes can cover sticky sand saturated with water. Any careless manoeuvre would waste precious time getting out of the trap of the incoming tide. Each burying may result, at best, in the threat of losing the car. There is nothing to which a rope could be attached from a winch nor anything to use with the aid of a second car. That is why stress levels are high. We can rely only on ourselves, the shovels and the planks. Driving the Doodsakker, we are buried once, but thanks to the experience we acquired earlier we were quickly able to extract it from its wet trap.

After less than two hours, we reach the height of the island. On the horizon, the outlines of abandoned buildings 8 kilometres away can be seen. Soon, the tide begins to come in and so we look for a place where we will be able to safely park the car. There are some small dunes which we are able to drive up and leave the car without worrying about the incoming tide.

SAO MARTINHO DOS TIGRES

The last, nearly 8 kilometre stretch leading to the island is completed by boat.

Many people interested in abandoned places ask me which places – besides the Chernobyl Exclusion Zone – I could recommend to them. I reply then that I have rarely visited other places, because they do not interest me in and of themselves. I’m not interested in the ruins of buildings, empty spaces or the objects left behind. I’m interested in the story that lies behind them. Or the stories of the people who once lived here. And if that is associated with tragic events, human drama or is just simply interesting, that it is worth telling, I have a reason for my next trip. It was the same with Sao Martinho dos Tigres.

The beginnings of the city, then still a settlement located on a peninsula surrounded on one side by the ocean and on the other the desert, dates back to the 1860s. It was then that the early settlers came to the peninsula neighbouring the Baia dos Tigres. These people were encouraged by the richness in fish of the surrounding waters. Initially, the fishermen took their own food and water supplies, with had to be enough to complete the more than 100 kilometre journey through the desert and then for the time they fished and for the way back. Later, water was obtained on the land part not far from the gulf, from two ponds in a hollow in the dunes. The water from there was awful, however. It tasted bad, had a laxative effect and caused liver and kidney pain.

It is difficult to imagine the dedication of the people who spent years there. In a place where it does not rain, where there was no drinking water, where there was no wood to use to keep warm or cook something. In a place where the wind was always blowing, and clouds of fine sand got everywhere. They breathed it, ate it and drank it. But the cold, plankton-rich waters of the Baia dos Tigres as well as the resulting abundance of fish were the factor that trumped all the hardships a person could find there.

It was only with the passage of the years and the subsequent influx of settlers that the lack of drinking water became a barrier to the town’s further development. The fishermen tried to bring it in by boat from Moçâmedes, having earlier sold dried fish there. Due to the difficult weather conditions it was, however, an extremely difficult and hazardous task. They also tried to transport water by large ships, but often the payment demanded for it and its transport was higher than the residents could pay. The irregular transports, which often got lost or were late, brought about the rationing of this precious liquid. Very often, the water was saved up from the moment it was received. The daily limit of several cups was enough to stave off death from thirst. The chronic lack of water led to it being treated with almost religious reverence. Each arrival of a boat with water was treated as a major holiday. It was full of rites and preparations – they cleaned the beach, prepared their best food and donned their most festive clothes.

Almost 100 years later, the Portuguese authorities finally surrendered in the face of the courage and selflessness of the inhabitants, who were prepared for sacrifices, hard work and extreme poverty. In the early 1950s, they built several public buildings that helped in the creation of a genuine human settlement: a hospital, school, post office and a maritime office. The buildings were built maintaining adequate distances from each other, many were on special poles and platforms to allow for the free circulation of sand picked up by the strong wind known as the garrôa. They also built a church, the architecture of which resembled a cathedral; for the people it was a vigilant sentry, a guard and protector in which nothing bad could happen. But the problem of the lack of water still did not allow the residents to pause for breath. To feel safe. That is why it was soon decided to pursue a very expensive and, because of that, long-postponed plan to build an aqueduct connecting the peninsula with the River Cunene, 80 km away. Even before it was completed, new factories were built on the island and old ones were modernised, and the population grew to 1500 people.

When construction of the pipeline was completed in 1962, it seemed that the problem of water had finally disappeared. Residents could drink better water, bathe and wash their clothes. It seemed that nothing could stand in the way of the town’s further development. Unfortunately, the water in the taps of Sao Martinho dos Tigres ran only for a few months. That same year, the inhabitants of the Baia dos Tigres were again rewarded for their efforts and dedication with misfortune. A natural phenomenon, which turned out to be cyclical, caused a rupture in the sandy banks of the isthmus at the point connecting the peninsula to the continent, destroying the pipeline. Overnight, the water stopped flowing and the peninsula became an island.

Just after the disaster, the government was forced into immediate action; it was obligated to purchase a tugboat. Its task was to tow the barges to the mouth of the damaged pipeline, where it was filled with water and transported to the town. At the same time, attempts were made to find a solution to the problem with the pipeline. One that would guarantee that a similar problem would not happen in the future. Unfortunately, they could not solve the problem over the next few years. The slow exodus of residents began. Its culmination was in 1975, on the eve of Angola obtaining independence, before the fire of independence movements and in an atmosphere of complete anarchy, all of the inhabitants of Sao Martinho dos Tigres had to leave the island. The outbreak of the 25-year-long civil war finally determined the fate of the town’s inhabitants. They did not return to the town, even after the end of the war. The lack of water proved to be an insurmountable obstacle.

FILM

No picture renders the prevailing atmosphere on an expedition better than film. That is why I also took a video camera with me.

MEDIA ON THE ANGOLA EXPEDITION

Some news stories and short reports broadcast in the Polish media (only in Polish).

WANT TO KNOW MORE?

During my two-month stay in Africa, I visited many more interesting places. If you would like to see unpublished photos or keep updated the preparations for my next trips to Africa, Chernobyl and Japan, add me as a friend on Facebook or choose the FOLLOW option.

WOULD YOU LIKE TO JOIN THE NEXT TRIP?

In March, I will return to Angola, from which I plan to go to Zambia and Malawi, and then to Uganda, Rwanda, Tanzania and Ethiopia. In May, I will return to Chernobyl. If you would like to join the trips to Africa or Chernobyl and have similar adventures, send an e-mail to arek (at) podniesinski (dot) pl.