PART 1 – THE OMO VALLEY

Do they always dress like this or is it specially for tourists?

We kept asking ourselves this the whole trip.

Who are we talking about?

The primitive tribes of the Omo valley. Tribes which we had previously only read about in National Geographic or seen on Discovery.

Now, with an SUV at our disposal, we could see them with our own eyes. Thanks to the car we could get anywhere, even the most distant and inaccessible places, without problems. Fitted with all the equipment essential for survival in even the largest desert. 4 wheel drive, winch, compressor, spare tires, extra gas tank, water, stove, tent, first aid kit, etc. If only I knew more about cars… :) But in the end the satellite telephone and GPS reassured me. In the worst case, we could call auto-assistance :)

And so we just had to top up the fuel tanks, food and water and the next adventure was before us…

With the car at our disposal, we could also splurge in another way. We took the whole set of photographic equipment with us, making it possible for us to take studio photographs wherever we were. I’m mainly talking about lighting equipment with independent power supply which made it possible to carry out professional photo sessions even in the middle of the desert. Instead of bringing the natives to Poland for a session, which is technically and financially impossible, we organised picture sessions for them right where they live. The photo session came to them.

You can see the results of this in the gallery, but only after you’ve read the whole photo-report :)

If you don’t already know where the Omo River and valley are, I will explain. – southern Ethiopia. Primitive tribes live there: the Hamer, Mursi, Dassenech, Karo and many smaller ones which are hard to even locate because they lead a nomadic lifestyle. They set up camp in one place only to be somewhere completely different the next year. These tribes are a relic of the past, a time and tradition which in today’s world, under the influence of incoming tourists, is quickly disappearing. Additionally, the completion of roads leading to the places where they live further speeds up this process. We don’t have too long to wait for the first effects. Nails received from visitors act as earrings for women, bottle caps decorate women’s heads and watch bands fill the role of pendants hanging from necks. The tribes have learned the value of money and don’t just use it for trade amongst themselves, but also charge for posing for pictures.

At the same time, near where they live, one of the largest water dams in Africa has been built. Hardly any of the simple inhabitants of the Omo valley are aware of the effects the dam will bring. That the dam will disrupt the flow of the river which irrigates the nearby farmland, that the tribes’ abilities to cultivate and collect a sufficient amount of food will deteriorate. Some tribes are already struggling with periods of hunger.

The tribes, until recently cut off from the world, are starting to change. So this is the last moment (if it is not already too late) to capture them in the state in which they have lived for hundreds of years. Soon this will surely all change.

At the same time, we have a moral dilemma – are we not contributing to these changes by visiting ourselves? Should we make the local tribes “happy” by bringing in new technology, medicine, electricity, building roads, dams, and at the same time destroying their culture that reaches back a thousand years? Or maybe the opposite – should we leave them alone with the knowledge that there are still people living in the world untouched by modern civilization?

Of course all cultures, whether they want to or not, evolve under the influence of time, or one influences another. It is an ongoing process over which we often have no influence. Like how did Halloween or Valentines Day start with us? But if we have no influence on it, then let’s at least be aware of the effects it could bring. This will come in useful during visits to places that are so different from our culture. And so, having finished the educational lesson, time to get down to the heart of the matter. I mean, of the journey :)

HAMER – beautiful, colourful

The first, and most populous, society of the Omo valley which we reached is the Hamer tribe. This pastoral-agricultural people is famous for its customs which are not encountered anywhere else. The most known of these is the custom of jumping over bulls. Every boy when reaching maturity must undergo this ceremony, which the whole neighbouring population attends. Several dozen bulls are placed beside each other and friends of the jumper, but only those who have already passed this test, ensure that the bulls stand still. The task involves the young man, naked, running along the backs of the bulls several times. If he successfully passes this test, he can get married. Unfortunately I didn’t manage to find out what happens if he slips :) However, this is not the most exceptional part of the whole ceremony. There is still a bloodier part, as is usual in such a case, with the participation of women. As it soon turned out, this is neither the first nor the last ceremony in which women play the main role. Why do women always have to get the short end of the stick? During this ceremony, the men beat the women with thin, pliant rods. And the women voluntarily agree to this. Not only that, but they insist on it, running up to the men several times and asking for more. Participating in this ceremony, we learned that in this way the women want to show their love and devotion to their brothers. And you know how it is in Ethiopia, they often have a lot of these brothers. Women have it easier where we live. For me, for example, if a woman wants to show me love and devotion, it’s enough for her to bring me a cold beer ;) She doesn’t have to sacrifice so much at one time.

The women of the Hamer tribe also stand out for their beauty and clothing. And the men aren’t so bad either, sporting fanciful hairstyles on their heads. When they kill a dangerous animal, and at one time an enemy, they would wear a beautiful bun on their head decorated with an ostrich feather. Interestingly, every other Hamer has some sort of feather in their hair so they are either pulling the wool over our eyes or I now know why you never see any predators in the wild in Africa. Also, the women have identical hairstyles. A weave of hundreds of small wisps which are then stuck with clay and butter. Unfortunately this is at the cost of serious sight problems later for the women when, during the notorious heat waves, the clay mixed with sweat drips directly into their eyes causing blindness.

A dozen or so inhabitants surrounded us in the village. Some were simply curious, others wanted to sell something, but the largest group was locals who asked us to photograph them. Unaware of the trick, the tourist thinks that a brilliant occasion to take pictures has presented itself. Of course soon after he is very confused when right after the snapshot the local holds out his hand and says “tu birr”. This whole racket just disrupts leisurely picture taking. That is why in every village, before we took out any photographic equipment we first approached the chief or one of the elders. We would greet them, explain the purpose of our visit, ask about consent for taking pictures and of course establish an appropriate payment. And it is with the latter that the most problems arose. We were prepared to pay for photos. However, we didn’t assume that it would be necessary to pay for entrance to the village or for hiring a local guide. It didn’t matter that we had our own.

If you really think about it, it’s hard to be surprised by them. Turning the situation around, if some foreign looking people came to my home, at first I would definitely greet them politely, wave my hand, occasionally invite them in. But if it was every day? Then I would definitely put up a barrier and start to charge a fee.

And that’s just what they did.

And furthermore, they are meticulous. They listen and count the number of snaps of the shutter or watch for the number of flashes. If, god forbid, someone accidentally appears in the background, you have to pay them too. If a woman happens to be feeding a baby, the baby also counts as a person. Now you know why you don’t find group photos from this region on the internet :) And to think – not long ago you could just greet them, smile, and ceremoniously hand over some trinket…

Those who are paying attention will ask how we made ourselves understood. Indeed, we hired a local guide who was born and grew up in one of these villages and then went to a larger city where he learned English. Not in any school, mind you, but from films, books or conversations with tourists. After all, for us he didn’t have to speak fluent English, as long as he was fluent in the local dialects and there are many of them because Ethiopia is a country of 80 languages.

MURSI – belligerent decorators of the body

The Mursi are probably the most wild and most belligerent tribe of all those that live here. Their appearance is completely distinct from other tribes. Mainly due to putting clay plates through their lips and ears. We were told that these are a sign of beauty and health. It starts at a young age with making an incision in the lip and inserting a tiny disk which is replaced with an increasingly large one according to age. Sometimes two front teeth are also removed to make it easier to insert.

We had previously read a little bit about the Mursi, so going to their village we knew not to take any valuables, ornaments, bracelets or watches which could be “collected” from us when getting out of the car. Everything should remain in the locked car. Additionally, through most of the day the Mursi drink homemade alcohol, so it’s best not to visit them in the afternoon when they are in the greatest state of intoxication and can simply be dangerous.

Did I tell you that they are also armed?

That is why it is obligatory when in the Mursi’s region to hire an additional armed guard. An obligation is an obligation so we hire one such guy with a rifle. We think surely he’s already visited the Mursi hundreds of times so he’s acquainted with them and it will be easier to meet with the village chief. We later see how fruitless those hopes were. But let’s not get ahead of ourselves.

In the first Mursi village the chief appeared. With a cloudy, indifferent gaze. Drunk, of course. It wasn’t better with the rest of the inhabitants of the village. It was hard to recognize from their facial expressions if they were friendly or simply waiting to do something to us. Okay, I thought – they must earn their renown somehow :)

The drunken chief demands a sky high fee for photos. We thought, calmly, we were prepared for that. We knew that the Mursi value themselves higher than other tribes. As a rule, they want several times more. But here evidently rules aren’t binding. The chief wants several dozen times more! Negotiations, which under normal circumstances shouldn’t take more than a few minutes, seemed endless. It also had to do with our equipment, especially the lamp which they took for a camera. We showed, explained, we could even shine it in their eyes. Finally it seemed that everything was okay and the heated atmosphere subsided. At least until the moment of payment for the first series of pictures. After handing over the money, it turned out that photographing people requires 5 times more. He threw the money in our faces. Our explanations that we had already agreed on a fee were for nothing. No effect. Did we have to start everything over from scratch? Of course we didn’t agree to pay more than the amount established, which resulted in one violent gesture by the chief after which all the inhabitants suddenly disappeared. Even we could guess that meant only one thing. The end of photographs and the visit. So we politely packed up our equipment and returned to the car. Being in the middle of a village, surrounded by several dozen indifferently watching natives is no laughing matter. Not to mention the drunk and armed chief. There was too much playing on our nerves, better to get out of there. Unfortunately, leaving didn’t turn out to be as simple as entering. First we had to pay for entry to the village. So what if we had hardly entered it and didn’t take pictures. It was enough that we entered the terrain. Again cries, threats that they wouldn’t let us out. They didn’t let us close the doors. We tried to keep cool but the situation was becoming increasingly tense, especially since 4 armed musclemen were standing in front of the car. And our superhero guard, who at that moment should have jumped out from behind the bushes, waved his shotgun and helped us, was quietly waiting off to the side. He was hoping that everything would end well on its own. Of course it wasn’t worth the risk, we paid and set off. But we didn’t give up. We tried the neighbouring village whose inhabitants seemed friendlier (read: sober).

This time, having learned from previous experience, we didn’t go into the village before finishing negotiations. We started by showing our equipment. We showed the flash lamp and tried to explain why we needed it when the sun was already shining (I invite you just to try explaining that to them yourselves!). We patiently explained why we had that large silver umbrella. Despite all that, they didn’t really want to agree and we didn’t really want to insist in light off the recent incident. Discouraged, we gave up, but we also grasped at one last resort. We returned to the car and pretended to pack up the equipment. It worked! Scared that we would leave without leaving even a penny, they changed their mind. In other words, everything was clear even without the help of a translator. If you don’t know what the problem is, the problem is money. Then it went smoothly…

And after the visit in the village of aggressive and dangerous Mursi, every following visit was a pure pleasure.

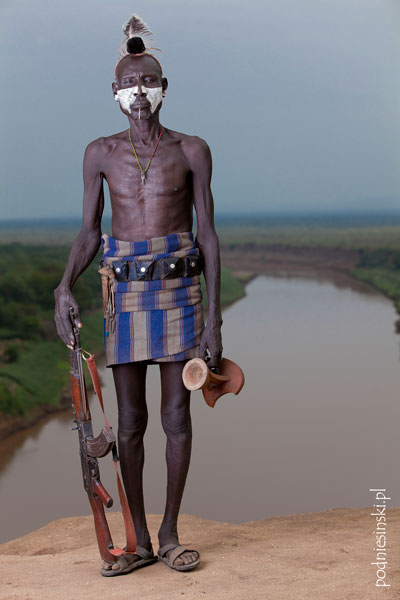

KARO – attractive scars

Reaching the place where the Karo tribe live took a lot of time. The paper maps normally available only have outlines and did not include any of the roads we were travelling on. Of course we had GPS, but this also didn’t have a map of this region and was only good for indicating the direction we were currently heading in. It was also good for remembering roads we were on in order to go back in case we got lost. First we tried to reach it from the north through the national park. At first the visible tracks of previous cars made it easier for us to search for the right direction. However, in time the visible tracks started to go off in different directions or disappear completely. All the ones we tried eventually changed directions and led in the direction we had come from. We decided to go back and try to reach it from the south. Two days later we found the right road that led us to the fabulously set village of the Karo tribe. Situated on a high escarpment with a view of a bend in the Omo River, it enchanted us at first sight. An excellent place for a session. And in the mean time, breakfast with pancakes right from the village. Which we had to pay for, of course. But the beautiful view of the Omo valley was free. Of course, only as long as the chief didn’t come and check for an entry ticket. And offer his impartial help, for which he also wants money. You can get used to such folklore. The whole surroundings are so beautiful and picturesque that we wanted to stay there much much longer. The holidays are just around the corner so we sent a Christmas postcard :)

The Karo tribe, to which we were paying a visit, is famous for the fancy notches on their bodies. They sprinkle ashes on the extensive cuts so that protruding, highly visible scars form. For men, such scars are a mark of killing an enemy during battle. For young women who also scar themselves, they are a mark of beauty and attractiveness. Members of the tribe also know how to decorate their bodies in less drastic ways, using chalk and natural dyes. They know how make themselves up in such a way that from a distance it’s hard to recognize them as people.

DASSANECH – bloody ceremonies

The Dassanech are most southern tribe, located just along the border with Kenya. Despite the proximity of the river, this region is one of the driest in the Omo valley. Its inhabitants are able to survive only thanks to the river and specifically thanks to its floods which periodically irrigate cultivated land. After several hours driving we found this place. It turned out that all of the Dassanech tribes live on the other side of the river and the only bridge that was ever here was destroyed several years ago in a flood. So we looked for a boat which we could take to the other side. This didn’t take much time. We found a man who provided a boat who for a small fee, 50 times higher than for the locals, agreed to take us across. Made of one piece of a tree trunk, it looked totally solid. So what if it leaked a bit and rocked terribly side to side. We loaded the equipment and were on our way.

The Dassanech were another tribe in which women had a hard life. The custom of circumcising ten year old girls is prevalent in the tribe. Without circumcision, there is no chance of finding a husband. And if she doesn’t get married, her father doesn’t receive the customary dowry. And so the father is actively “engaged” in making his daughter go through this horrible torture. The cut is made quickly by the oldest woman in the village, the girl is held down and her legs are tied with leather strips. The girl lies tied this way as long as the wound keeps bleeding and until pain subsides. Only after the ceremony does the girl have the right to wear a leather dress, a sign of adulthood and maturity for marriage.

Women from the Dassanech tribe, like the Hamer, are distinguished by exceptional beauty, slender bodies and regular facial features. Almost every woman is worthy of a portrait… When we add to that the extraordinary clothing, and sometimes lack thereof, we have an excellent model. A model who, instead of a dress, wears a real leopard skin. Does this, by any chance, solve the puzzle of the ostrich feathers?

HAMER – the farther the better

We usually pitched the tent in the middle of an empty space, at least it always seemed that way to us. After a while, from out of the blue a native appeared. One evening one of them invited us to his village. When we politely declined, he disappeared and came back after a moment with food. It looked like dry lumps of earth mixed with green leaves. What’s mine is yours, I thought. In such a case it would be extremely impolite to refuse a meal, so like it or not we had to try it. In these cases I usually slink away under the pretence of pitching the tent or some other thing I wouldn’t normally be doing. And when they offer local alcohol, bubbling from the fermentation of brown gunge, with the look and consistency of grated raw potatoes, I saw I’m driving. Do you think they fall for it? So what if there are never police there, let alone breathalysers. After all, rules are rules everywhere :) And when I have no more arguments then I send Jola to the frontline – the best taste tester in the world :) For example, on the first day of our stay in Ethiopia she tried a local dish called kitfo. Something of an Ethiopian delicacy. Lightly heated, it resembles heavily spiced meat with beans. To this a white mush is added which looks like cottage cheese along with something resembling green grass. At first Jola willingly set about eating it but with every bite that will left her. Unfortunately it was very hard to back out as the chef kept coming out and asking how she liked it because he went to such trouble :) So what could we do? But that was just the start of the fun. Reading the guidebook in the evening we came across a description of this dish: “beware of kitfo, raw meat often contains tapeworms or other parasites”.

Could it be that Jola had found a new friend?

But returning to the subject at hand. Jola politely tried what the Hamer had brought which turned out to be the beginning of a Polish-Ethiopian friendship. After a moment Jola repaid him with bread and jam. Add to that some pot from the guide and the party was underway…

When we went to sleep our guide was still flying somewhere above New York singing some local melody. And our new Hamer friend decided to spend the night to make sure that it would be safe. I won’t speculate as to whether that was for him or for us :) Every night we slept by ourselves under the open sky and nothing ever happened to us. But we weren’t about to protest.

Darkness, peace, quiet and millions of stars not overshadowed by any big city lights. And the songs of the Hamers coming from the distance…

The real Africa.

And in the morning we delicately reminded our Hamer brother that yesterday he had invited us to his village…

ERBORE (ARBORE) – beauty in its pure form

The longer we were in Ethiopia, the better we got to know the terrain and customs. That’s why, encouraged by the unusual hospitality of the Hamers, we decided to deviate from the common paths (and are they really that common?) and go to even more distant villages. This is how we reached the village of the Erbore tribe. The lack of men immediately caught our eye. They probably all worked in the fields. These fields must be terribly far because there were no people as far as the eye could see. But that didn’t bother us at all because women were the reason for our arrival. Distinguishing themselves from other tribes by their clothing, abundance of beads and large black scarves. Younger, unmarried girls have shaved heads. We also learned that when a man wants to marry, he must offer the girl’s family several dozen heads of cattle. And the girl is circumcised on the day of the wedding. As if it were some sort of prize or great wedding gift.

The Erbore were the last Omo valley tribe we visited. It turned out that the inhabitants of more far-flung villages were friendly. More hospitable, unselfish and more curious about our journey. They didn’t try to sell us anything. It was obvious people very rarely, if at all, reached them. And they continue to look the same. Finally that worry we had before the trip that the natives painted themselves and dressed especially for tourists was dispelled. They were completely natural. The differences were somewhere else. In the most distant places there are no additional guides or entry fee! The way of life of the inhabitants has hardly changed in hundreds of years. There was only one thing they were not able to prevent. The flow of tourists and the consequence of money which greatly changed the inhabitants of the Omo valley. Having learned the value of money, they make us pay for everything. Money earned this way is most often spent on the conveniences of modern civilization, purchasing clothing, food or medicine. Do we have the right to refuse them this?

PART II. NORTHERN ETHIOPIA –

churches carved into (from) rocks

DEBRE DAMO

In the dim and distant past, St. Abba Aregawi stood at the foot of three thousand metre high plateau.

– I will build my monastery here – he decided.

And then a huge flying snake flew down from the sky and carried him to the very top of the mountain.

So many legends. The truth is that to this day many legends endure about how the building materials were brought to the summit. The monastery is called Debre Damo and is one of the oldest and most important in Ethiopia. Cut off from the world, located in an isolated environment – a 2800 metre hill with a flat, truncated summit with an area of around half a kilometre squared. The only way we could get to the top was climbing along a 15 metre line. Luckily it was a belay rope. I felt safe immediately. So what if the rope was made from raw goat hide. So what if it turned out to be held by a couple of kids when we got to the top. What’s most important is that it was there :) It’s better than how the monks have it, even the oldest of them don’t use any additional safety measures. In my amazement I don’t remember when I made it to the top. Luckily there is the film so you can see for yourselves. But Jola had it “best”, she avoided that whole adventure. For mundane reasons – women are not allowed to enter the monastery (so you see women have it worse even here). At the top we were greeted by father Zacharias – the guardian of the rope. It should have been him holding the belay rope, but clearly sometimes he just doesn’t feel like it.

At the top, not much has changed since the monastery was founded. They live there as they did centuries ago, before the Church had become institutionalized in a form overgrown with hundreds of commands. Christianity in its pure form, hardly changed since the beginning of the religion’s existence. The doors of the church were opened to us by the priest, who showed us the church and boasted of his old books.

ABUNA YEMATA GUH

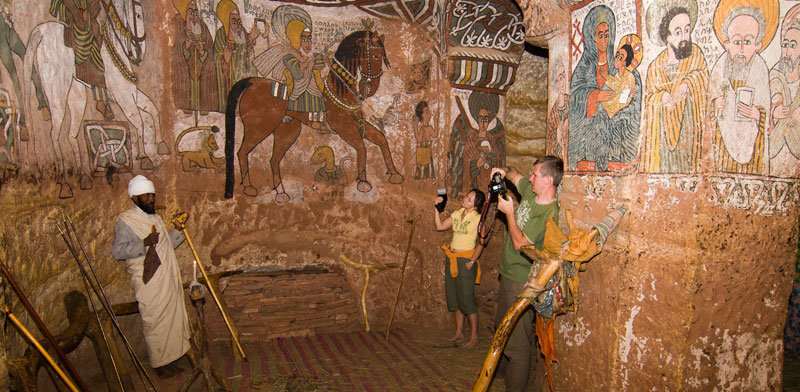

Visiting Abuna Yemata Guh was a completely different experience. The church is located in complete seclusion. No signs lead to it, we relied solely on a primitive map. We already recognized the place itself from far away by its characteristic high pillars. On one of them, at a height of several hundred metres, there is a church. Basically, the right word for it is carved out. A small church from the 15the century which is cared for by only one priest.

Unlike Debre Damo, there was no rope with which we could climb to the top. As you go in, the initially gentle slopes become steeper and steeper. In the last phase, they required all of our skills not to fall off the cliff wall. Below were several hundred meters of almost vertical cliffs and breathtaking views. That is, unless you are afraid of heights. At first we looked at the interior of the church where our attention was riveted by the wonderfully preserved frescoes. But for me the most significant thing was that here were no frescoes or portraits of priests. Before I went up the cliff I already had an image in my head: a shrine on a cliff and next to it a priest standing proud, meditative, with eyes fixed on the endless horizon. We just had to pick the most appropriate place. What was technically much more difficult was that we found ourselves at a height of several hundred metres, the wind was blowing quite strongly and in order to take pictures we had to balance on the edge of a pillar.

ABBA YOHANI

A very distant but fantastically located church. Cut out half way up a huge vertical cliff. We didn’t choose this church by chance, its picturesque setting was perfect for a session. The cliff face pointed west and so the setting sun further highlighted the red colour of the rock. In other words, a session at sunset.

It’s hard to find any information about the church itself besides that it was probably built in the 13th century. Despite its very isolated location, it is a living church. On holidays, many festivities are held here which believers from the whole area come to. They don’t have to go inside, it’s enough that they just stand at the foot of the cliff.

Access to the church is not possible from the cliff side as it’s too high and steep. In order to reach the church, you must go from the left side, where the slope is much gentler, then go through several tunnels, passing several rock shelves on the way. As a result, you reach the church from the side, directly from a hand-dug tunnel. Inside there are traditional frescoes, but not as great as in the previous church. The windows are cut out of rock and the sun’s rays shine through. There are several bats on the ceiling and to the side of the interior lie the bones of our priest’s colleagues. The most interesting thing for us is that from the church you can walk right out onto a protruding rock shelf from which an unbelievable view of the whole surroundings unfolds. There were still a few hours until sunset. We passed the time amusing the priest sitting next to us, looking at pictures together of places we’d been previously. It was a hit. The sight of other priests and churches which the priest knew only from stories meant that we didn’t even have to ask him to pose. He was dying to try it for himself. To such an extent that friends disturbed by the prolonged absence of our priest came to see what was going on. And thus, completely by accident, we had a trio…

Unfortunately that’s already the end of the trip. And adventures about which I could write much more. And pictures which, despite everything, were not that easy to take. Carrying the equipment around, quarrelling with the natives, climbing and terrible heat. But it was enough to snap just once for all the problems to go away, like waving a magic wand.

You can see the film from the trip and behind the scenes footage from the photographic sessions below:

A few pictures starring Jola. They asked so we couldn’t refuse:

And finally, we would like to thank Przemek for the use of his car without which this whole trip wouldn’t have been possible.