Cosmic dreams

Who didn’t dream as a kid of becoming a firefighter, policeman or doctor? I dreamed of being an astronaut since I was eight; I conquered the universe alongside Gagarin at the Cosmonaut Museum in Moscow. Several years later, as a regular reader of the popular science magazine Delta, I followed the traverse of Halley’s Comet across the horizon with bated breath using a homemade telescope. Unfortunately, no one becomes an astronaut simply by dreaming about interstellar travel or having an interest in astronomy. Including me. All of my youthful memories were revived when I saw images online of incredible, never-before-published photographs of the abandoned Buran space shuttles.

Impossible to be true

The first thing that occurred to me at the time was if it was even possible that these unique, historically and financially valuable orbiters, the source of great pride for all participants in the Soviet space program Buran — from scientists and designers to future cosmonauts — had simply been abandoned in a hangar somewhere in the middle of the Kazakh steppe. Why, instead of allowing them to shine in a museum and bear witness to Soviet cosmic thought, had they been condemned to such a slow death and the disgrace of thieves and vandals?

To answer these questions, we need to go back to the beginning of the creation of these fascinating machines.

The forgotten history of Buran

The Buran shuttle began to be constructed without a clearly defined goal. In principle, it was created solely as a response to the American Space Shuttle, the military potential of which was a source of concern for the Soviet Union. It was suspected that it could descend from orbit and drop atomic bombs on the major cities of the USSR in less than four minutes, much faster than what was possible using ballistic missiles fired from a submarine (10 minutes). The second concern was that the American shuttle could put a laser weapon into orbit that could destroy enemy missiles from a distance of several thousand kilometers.

Soviet leaders headed by Brezhnev, in order to prevent the military applications of the American shuttle, which was treated solely as another product of the arms race between the USSR and USA, decided to build a vehicle of similar size. In this way, they were confident that they would react adequately to any mission conducted by the Space Shuttle.

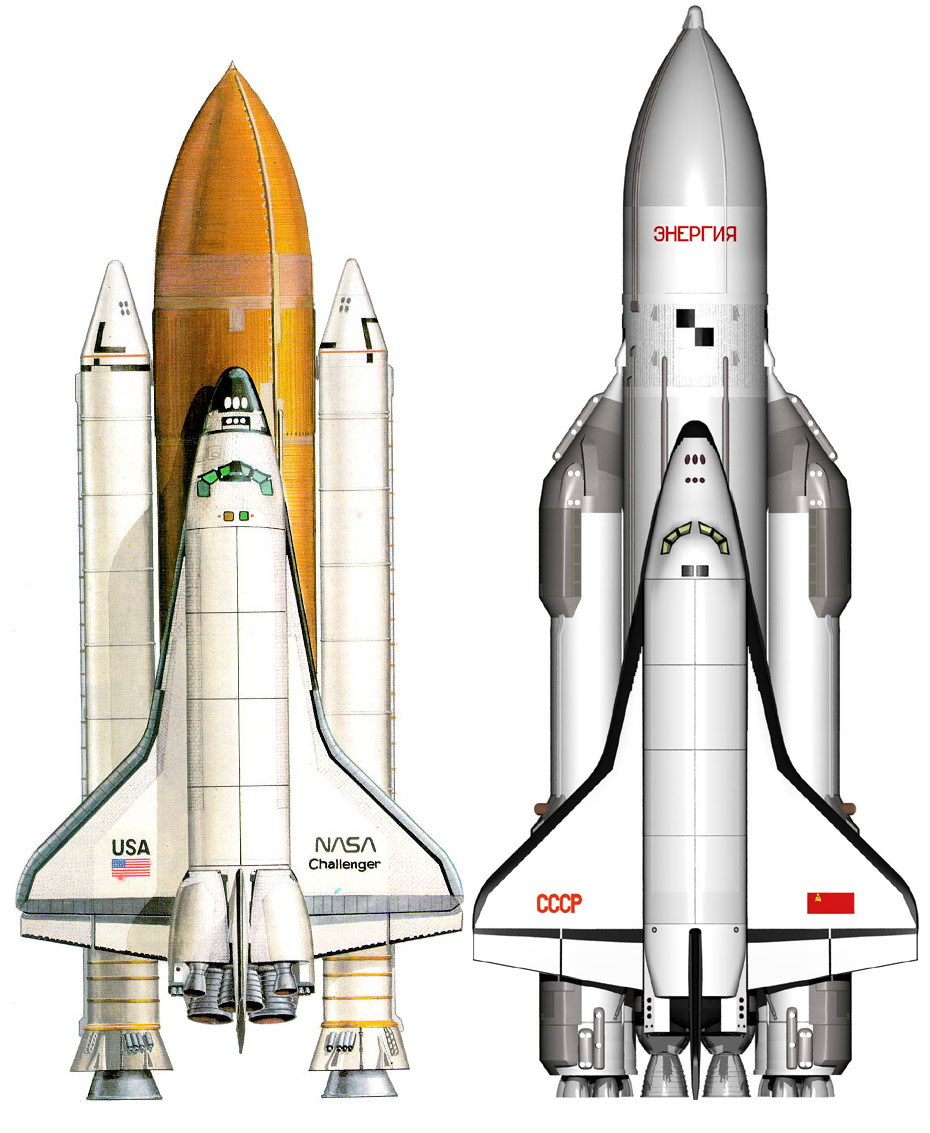

Space Shuttle vs. Buran

Copying many solutions from the Space Shuttle allowed the Russians to use the Americans’ experience and saved time and money for research and development. However, they had to develop and test technology, materials and the entire infrastructure themselves, and in order to do so often followed their own unique path. The American version of the shuttle consisted of an orbiter equipped with three powerful engines and an external fuel tank attached to it. In the Soviet version, the main propulsion was shifted to the Energia rocket so it could be used for other missions. A significant difference was that Burans also could run fully automatic unmanned space flights and had ejectable crew seats to ensure greater safety. As a result, in many respects the Russian solutions proved to be better or more universal.

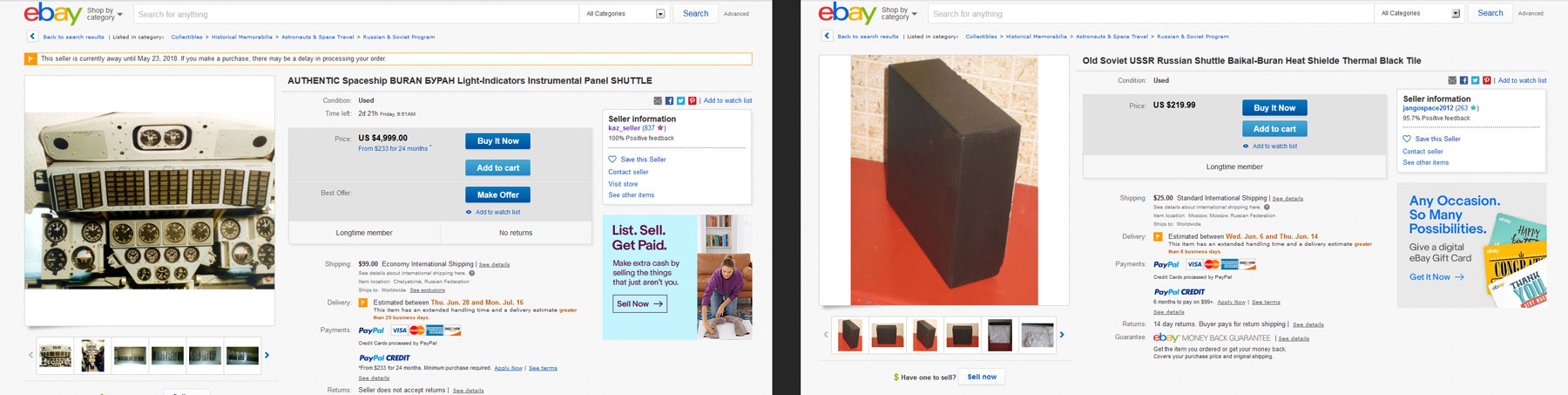

Several dozen rockets and test models were built or began to be built as part of the Buran program. 12 years after its official start, the first space flight was conducted using one of them (15 November 1988). Other, more complex flights into orbit were also planned. However, the end of the Cold War and the collapse of the Soviet Union led to the 1993 decision of President Boris Yeltsin to officially end the program. Soon, unnecessary devices began to be sold or scrapped; they were also used in other space projects. Several Buran test models ended up in museums, and those capable of launching into orbit remained in the Baikonur Cosmodrome. Unfortunately, fate was not kind to the first and only orbiter that managed to reach the cosmos. In 2002, due to poor maintenance, the roof of the Assembly and Test Facility (MIK) building collapsed, resulting in the destruction of the orbiter and the deaths of eight workers. The remaining two orbiters were no more fortunate. Over nearly three decades they have been stripped of their most valuable elements, which have found their way to collectors from around the world. The photos of these orbiters are what aroused my interest.

Equipment from various Buran models is sold on eBay to collectors of space souvenirs from around the world

My conversations with the employees of the Russian Space Agency and the Baikonur Cosmodrome about the reasons for this state of affairs and the inability to legally visit the shuttles did not lead to clear answers to the questions that tormented me. That is why I decided to go to Baikonur on my own and check the current status of the orbiters. To take photographs of them and remind the world of their existence. Maybe someone will become interested and save them.

The legendary Cosmodrome

Located in Kazakhstan, the Baikonur Cosmodrome is the oldest (1955) and largest (6,000 km2) spaceport in the world. After the breakup of the USSR, it was leased to Russia for 115 million US dollars annually and is now under its jurisdiction. It is from here that the launching of the first intercontinental ballistic missile (R-7, 1957), first artificial satellite (Sputnik 1, 1957), first space probe (Luna 1, 1959) took place. The first manned space flight (Yuri Gagarin, 1961), the first flight of a woman into space (Valentina Tereshkova, 1963) and the flight of the first Polish astronaut (Mirosław Hermaszewski, 1978) all happened here. Finally, the base model for the Mir space station (1986) and the first module of the International Space Station (1998) were launched from the Baikonur Cosmodrome. And, what else? The first and only launch of the Energia rocket, which carried the Buran shuttle into space, also took place here (1988).

The Baikonur Cosmodrome remains an active and the most important base of the Russian space program, with numerous commercial, military and scientific missions. With the retirement of the American shuttle program, it has also become the only launch site for manned missions to the International Space Station; Russian spacecraft are used for this purpose.

A risky mission

Getting to the Burans, located in the center of the active and closely guarded Cosmodrome and surrounded by thousands of kilometers of the Kazakh steppe, is very risky and dangerous. Nearby, only a kilometer from the hangars, are launches for manned rockets heading to the International Space Station. The Burans, part of the unique heritage of Soviet cosmonautics, and the history they carry with them are, however, worth the risk.

The only way to get to the abandoned hangar is first to walk through the dry and sandy steppe approximately 40 kilometers in a straight line from the nearest public road. And then you have to return. All of this requires meticulous planning, equipment and the appropriate logistics considering all possible scenarios, as well as requiring the help of several locals who helped make the trip much safer.

The road to the shuttles takes two nights with a daytime break for sleep and rest in one of the many abandoned buildings located around the Cosmodrome. I move only at night, far away from any roads, checkpoints and active facilities. It is only in this way that I can pass unnoticed by the police patrols, guards and Baikonur employees. The worst, however, are the dogs that despite the pitch darkness can sense the presence of a person from afar and alert the guards.

One of the 18 silos located in Baikonur in which the long-range FOBS intercontinental missile launchers were located. In 1983, the orbital missiles were withdrawn from service and the silos destroyed as part of the provisions of the SALT II treaty, which forbade the use of this type of weapon.

The Assembly and Fueling Facility (MZK) where the abandoned shuttles stand

The hangar for the Dynamic Test Stand (SDI), where the Energia-M rocket is housed

When I reach the place after nearly two days and enter the abandoned hangar, the enormous risk and effort are rewarded with the amazing sight of shuttles emerging from the darkness in the glow of my flashlight. I’ve seen a lot, but never something so special. For a moment, I stand mesmerized, staring up at the huge orbiter. I can only appreciate its size up close. It is enormous.

With a very powerful flashlight, you can illuminate a huge shuttle

The second space shuttle at the rear of the abandoned hangar

The forgotten Burans

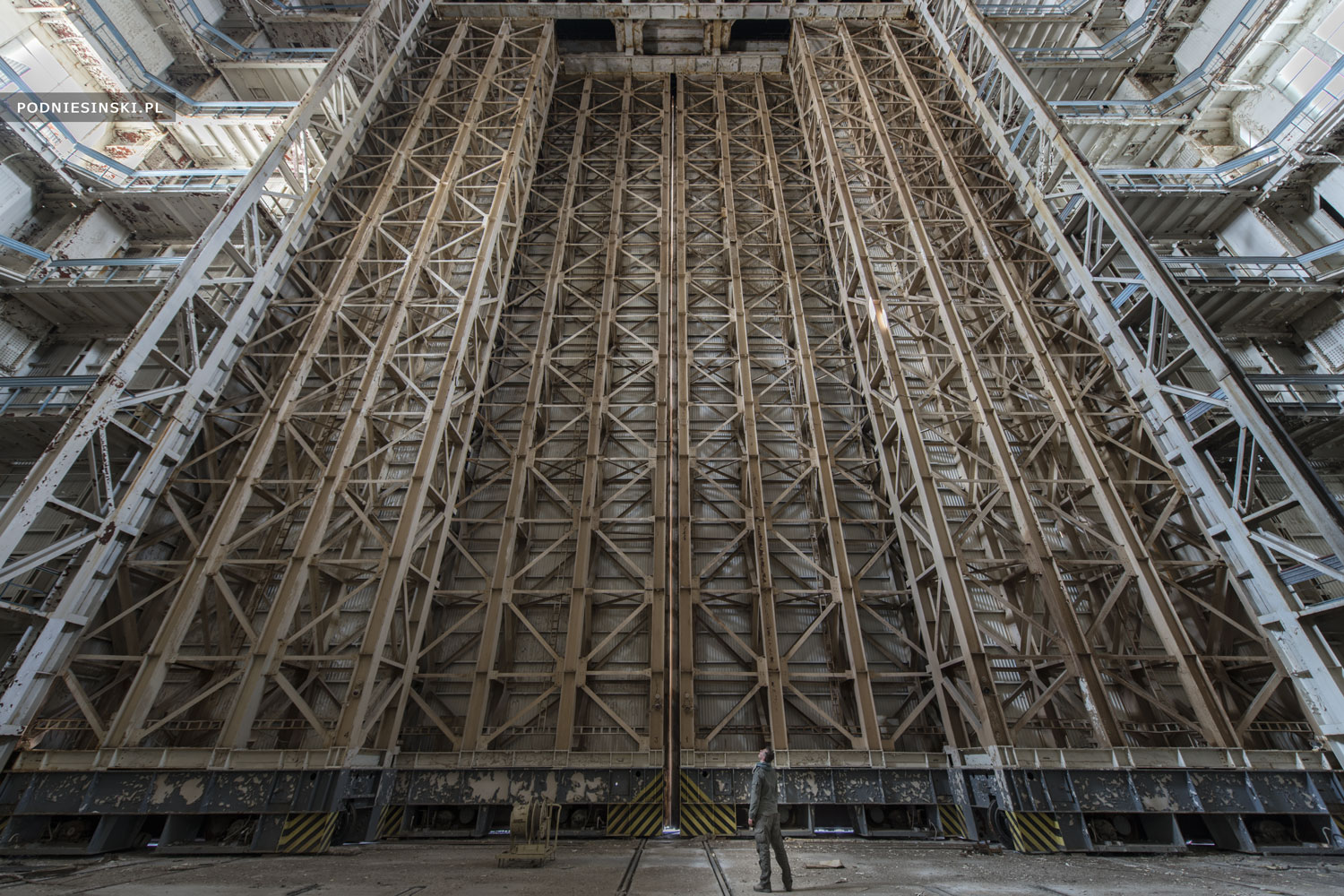

It is only with daylight that I can see the hangar and both shuttles in their full glory, and appreciate the enormity and complexity of the entire undertaking. The hangar of the Assembly and Fueling Facility (MZK), where I am, was specially designed for the refueling of the propulsion systems, supplying dangerous and easily combustible gasses and fluids. Here, pyrotechnic devices and loads were also placed into the shuttle’s loading bay. I try to imagine what this place would have looked like three decades ago, full of lights and the sounds of machines and devices at work, along with technicians engrossed in preparing the shuttle to be launched into space.

The OK-MT (front) and OK-1K2 (rear) space shuttles

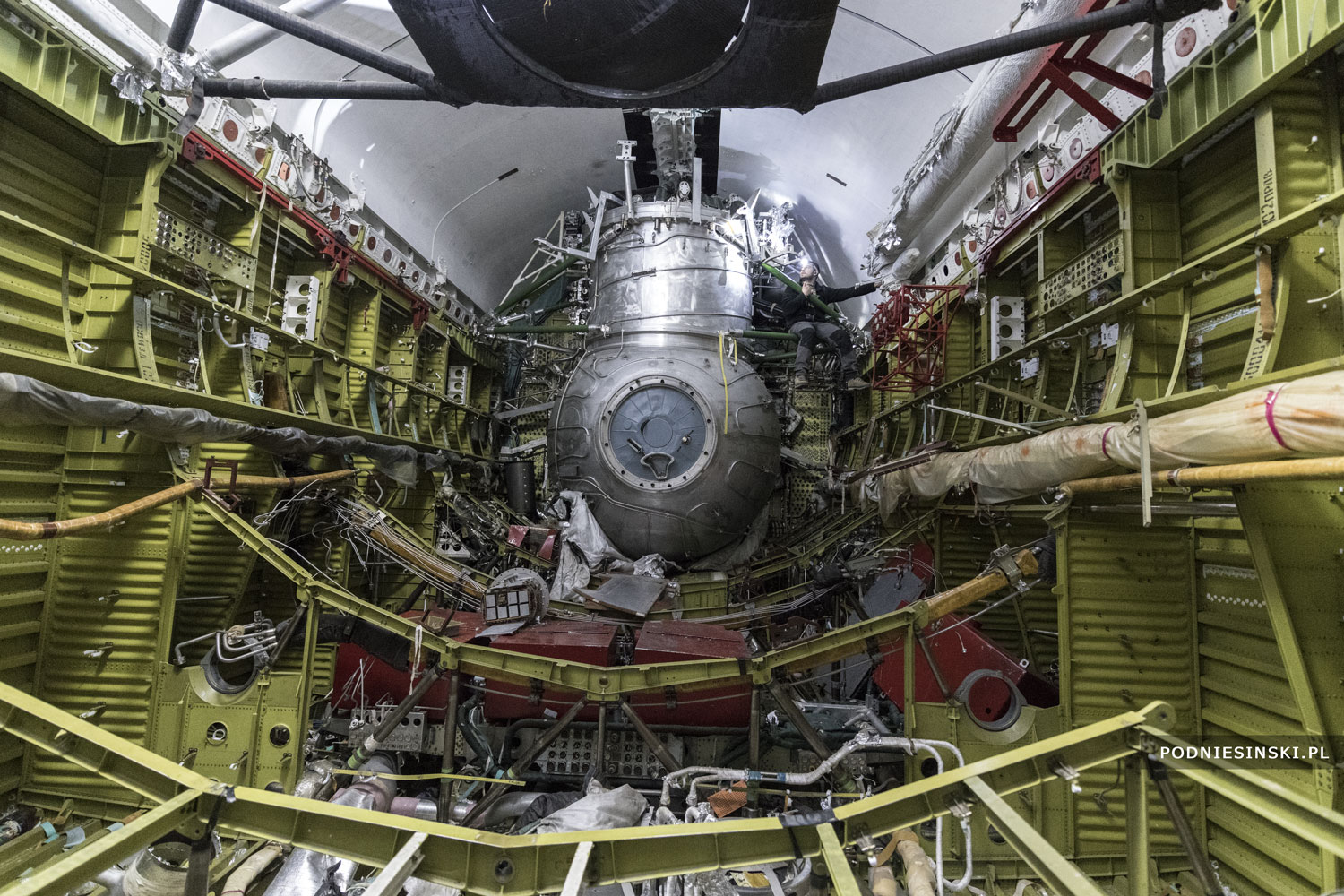

The Assembly and Fueling Facility hangar is filled with Buran tanks, i.e. the engine, the orbital maneuvering system and fuel cells. After fueling and installing the payload in the cargo bay, the Buran-Energia setup was ready for transfer to the launch pad.

The huge 70-meter sliding doors in the Assembly and Fueling Facility hangar

From the Russian-language literature on the Buran program, I learned that the shuttle in the front of the hangar is an engineering mock-up. This can be recognized from its lack of an orbital maneuvering system. The shuttle with the working name OK-MT was used for static tests, including the development of technical documentation, methods for crew evacuation, and the loading of liquids and gasses; after its transportation to Baikonur, it was used to test the operations of the connecting systems with the Energia rocket. Initially, however, it was to be used for a test flight and burnt up in the atmosphere during its descent from orbit.

The OK-MT orbiter was not built to fly into space, so no orbital maneuvering system was installed in it

The OK-MT orbiter

The gantry operator cabin with the OK-MT orbiter in the distance

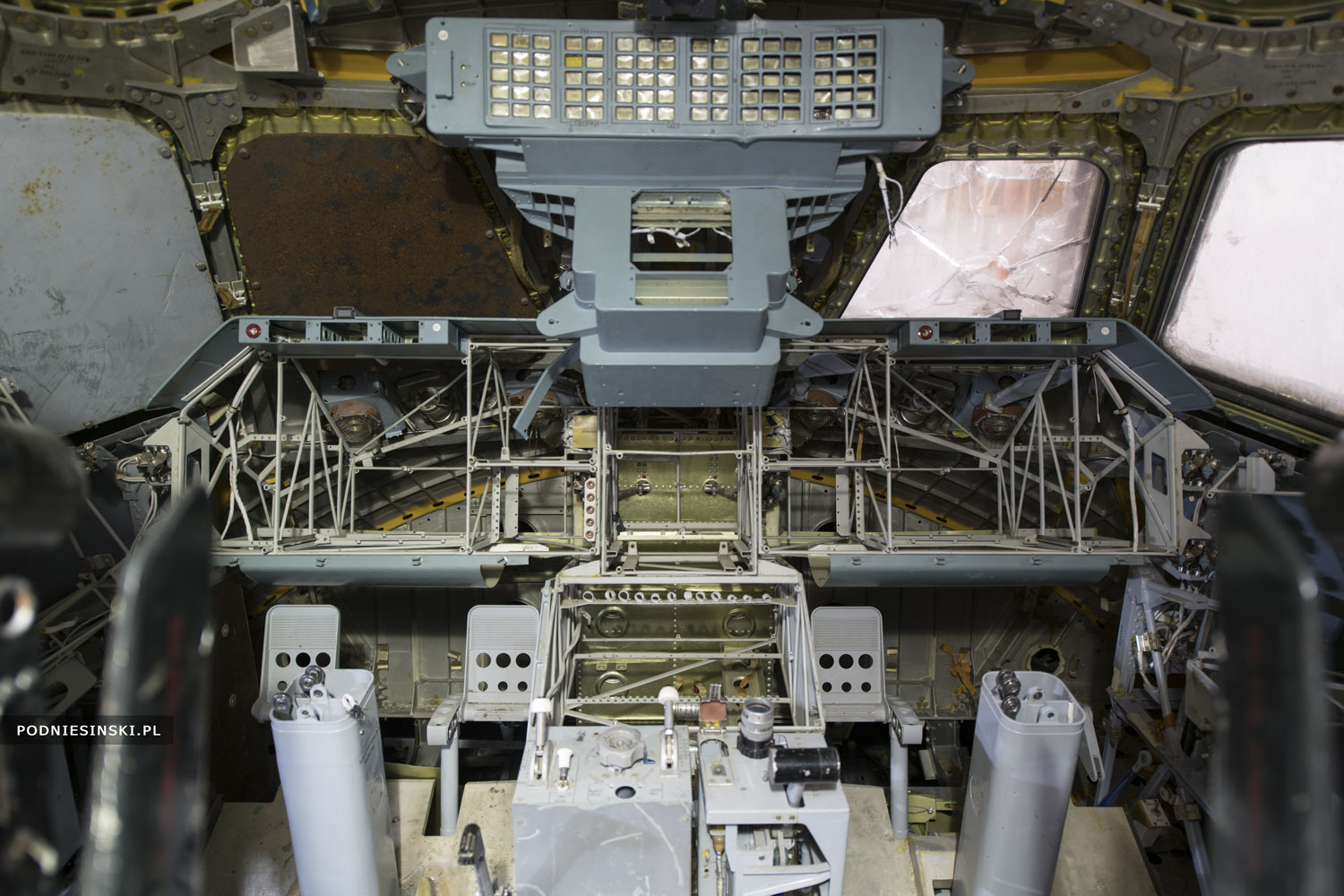

Due to its higher levels of automation, the Buran had significantly fewer control and monitoring systems in the flight deck than the Space Shuttle

Just behind this shuttle, however, stands a real orbiter — not a mock-up at all! The OK-1K2 is the second shuttle that was supposed to fly into space (after the Buran OK-1K1, which successfully did so in 1988). The task of the OK-1K2 was test docking for the Mir Space Station and Soyuz ship, as well as the transfer of crews between the two ships. At the time of the program’s closure in 1993, the shuttle was 95% completed, although when I look at the exterior, which has been pillaged by thieves, I do not see it at all.

The OK-1K2 orbiter

The hatch of the OK-1K2 orbiter. The photo also shows the side orbital maneuvering systems as well as black plates covering the shuttle’s nose to protect it during its entrance into the atmosphere.

Mid-deck of the OK-1K2 shuttle. On the right side is the hatch, and on the left is the entrance to the payload bay, and on top of the ladder the entrance to the flight deck.

Most of the devices in the flight deck have been stolen

The payload bay with the docking module located at the front. The spherical section had two bilateral hatches: one connecting with the crew module and the second with the payload bay used for spacewalks. At the top of the module was a retractable tunnel for docking to the Mir Space Station or the Soyuz ship.

The Assembly and Fueling Facility hangar is 150 meters long, 80 meters wide and 70 meters high. It was built on a metal construction designed to withstand a possible explosion during the dangerous fueling operations.

The room where the refilling processes for the Buran tanks were controlled

Technical workshop

The next day I visit a second abandoned hangar, located a few hundred meters away, in which I find the dynamic testing stand for the Energia rockets. Vibrations and resonances similar to those a rocket could experience during the initial phases of flight were generated and monitored from the more than 100 meter high building.

The Buran Program complex. The Assembly and Fueling Facility hangar (right), Dynamic Test Stand (left) and the launch complex (in the background on the left).

The Buran launch complex was originally designed for the Soviet program for manned flights to the Moon. Four N1 rocket launches were carried out here (all unsuccessful — one of them caused the greatest non-nuclear explosion in the world). From this site, on 15 November 1988, the first and last launch of the Buran shuttle took place.

The inside of the hangar conceals the second half of the history of the USSR’s Buran program — prototypes of the Energia-M rocket. This is a younger, smaller version of the Energia rocket, which primarily differs from it due to its lower payload and having two boosters instead of four. The original Energia, the pride of Soviet design, was able to bring more than 100 tons — the 70-ton Buran and its 30-ton load. To show what a great technological achievement this was at the time, let me use the example of the largest-ever SpaceX rocket. Elon Musk boasts that his Falcon Heavy „is the most powerful operational rocket in the world by a factor of two, with the ability to lift nearly 64 metric tons into orbit.”

The Dynamic Test Stand hangar with a 1,000-ton Energia-M rocket, which could bring a payload of up to 34 tons into orbit (10 tons more than the Space Shuttle)

In the hangar there is a prototype of the Energia-M rocket, which differs from the ordinary Energia rockets by its smaller size and having two boosters instead of four

One of the dozen or so levels of the Dynamic Test Stand hangar

Despite the closing of the Buran Program, many technical solutions for the Energia rocket are still being used, including in Zenit rockets and the Sea Launch Project

The hangar of the Dynamic Test Stand has a height of more than 100 meters

I wonder how many such secrets are hidden in Baikonur. Unfortunately, the police patrols wandering everywhere and my exhausted water supplies do not allow me to uncover them before my return. The expedition ends in dehydration.

Everything in vain?

After the Columbia Shuttle Disaster (2003), and particularly after the closing of the US Space Shuttle program (2011), some American and Russian scientists have begun to think about resurrecting the Buran Program so as not to have to spend money on a completely new ship. These plans, however, have not come to fruition. Unfortunately, today the orbiters and auxiliary equipment have fallen into such ruin that resurrecting the program is no longer possible. The shuttles will never fly into space again. Perhaps, however, they can be saved from the tragic fate of their predecessor.

***

As of publication time, I have visited Baikonur and the abandoned

Burans three times.

When writing this reportage, I consulted the following books:

Ю.П. Семенов, Многоразовый орбитальный корабль БУРАН (1995),

Г.Е. Лозино-Лозинский, А.Г. Братухин, Авиационно-космические системы (1997),

Hendrickx, B. Vis, Energiya-Buran – The Soviet Space Shuttle (2007).

Wow this is more than fascinating… The things that never came to fruitation and are hidden away should be brought to the forefront if not usable at least to give the history of knowledge that these places exist … Thank you so much for sharing… if people don’t we would never be able to say … Yep it really did exist … Thank you again.

Oh my God this is fascinating! And the audacity to walk all the way in & out & shoot under flashlight. Thank you, amazing photos. Haunting.

I did my best to get the word out and other people are loving it:

https://www.cake.co/conversations/lLlW2Pd/the-most-fascinating-photos-of-abandoned-ruins-i-have-ever-seen

Does Reddit know about this?

Thank you for posting these photo’s and information. Lets hope both orbiter’s are saved or perhaps the whole area is preserved for the future ?

magnifique !

un peu triste que ces navettes ne connaissent pas un autre destin !

Your willingness to share these photos with others is remarkable. The amount of time and effort it took for you to gather these photos is beyond words.

For you to share these so openly after the fact speaks volumes. Thank you. These are by the best photos of the Buran Space Shuttle Program. Superb!