BELARUSIAN CHERNOBYL

In the popular consciousness, the Chernobyl disaster has been engraved as a tragedy in Ukraine. Everyone goes there to see the results of this tragedy. Still, few people realize that it was in Belarus where, through no fault of its own, as much as 70% of the radioactive fallout came down, covering nearly a quarter of the country. This area was too large to simply close, as was done in Ukraine. That is why only the most contaminated areas were evacuated, with 140,000 residents forcibly removed. In the other areas, Belarusians had to learn how to live in the shadow of radioactive contamination. Many of them continue to experience the effects of radiation exposure.

I am going to see how they are coping and what “their” zone looks like.

ZAPOVEDNIK

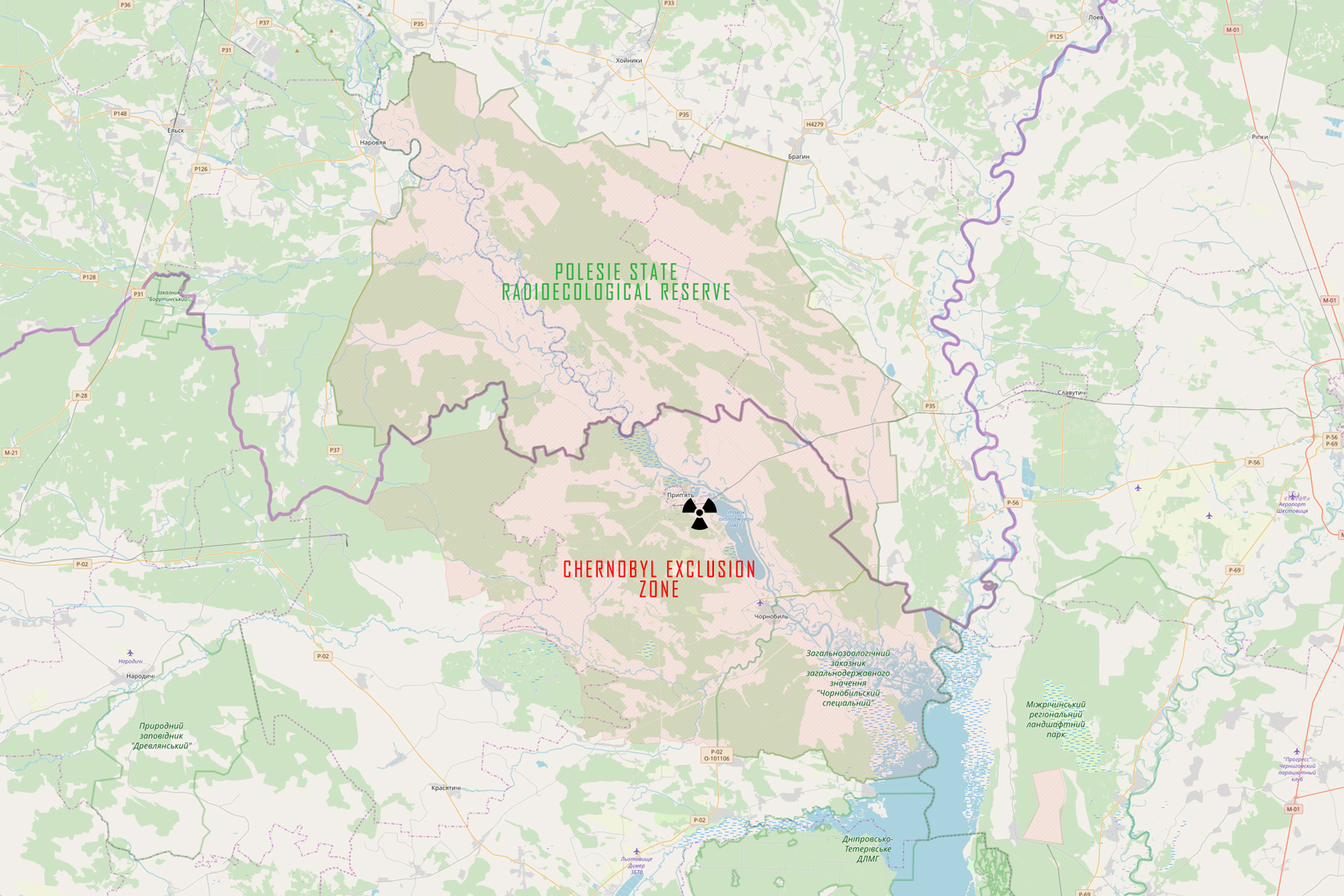

Soon after the disaster – as was the case in Ukraine – a 30-km zone was demarcated and closed, and more than 22,000 people were evacuated from approximately 80 area villages. Shortly thereafter, the entire area was fenced off with hundreds of kilometers of barbed wire, creating the 2,000 km2 Polesie State Radioecological Reserve, which borders the Chernobyl Exclusion Zone to the south. The reserve, popularly known by the Russian term Zapovednik (“nature reserve”), is now a unique laboratory for the study of the effects of radioactive contamination. Here, they monitor radiation levels, test methods of reclaiming contaminated soil and experimentally grow plants and raise animals. Due to the minimal human presence, the area is also incredibly rich in wildlife, many of which can be found in the Red Book, a register of endangered organisms. One can even find lynx and bison here.

Chernobyl Exclusion Zone and Polesie State Radioecological Reserve

School

Many houses and even entire villages have not survived. They were completely razed to the ground and covered over with sand, and those that remain today are a moving testimony to the Belarusian tragedy and the forced removals associated with the Chernobyl tragedy. Mother Nature, omnipresent and omnipotent, is ending her work, reclaiming what was originally hers. With the exception of one village where several multi-story residential buildings were built from masonry (due to their resemblance to the buildings in Pripyat, some call this place the Belarusian Pripyat), the structures that remain are clusters of wooden houses. It is difficult to find any items belonging to former residents inside of them – it is as though they had more time to evacuate and take their personal items. In some of the larger villages, there were schools, small shops and cultural centers built from masonry, but it is difficult to find in them any objects recalling the times before the disaster. Often, it is only the remains of furnishing like blackboards, desks or hanging posters that one can determine the specific purpose of a building. In Zapovednik, there are also no power plants, abandoned cities or landfills of contaminated vehicles. Thus, the reserve is not nearly as attractive as Chernobyl for extreme tourists.

School

Portrait of Lenin

Village cultural center

Shop

School

Gas masks in a school

The Moral Code of the Builder of Communism

Photos left behind

Masks

A calendar left behind – 6 May 1986, the day of the evacuation

Kindergarten – a doll left behind

Gym

Lenin monument

School – “No. There will not be a second Chernobyl!”

Abandoned border village

One of the hundreds of abandoned huts

Interior of one of the huts

Interior of one of the huts

Cemetery

View of the Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant from the Belarusian side

Leaving the zone

OUTSIDE THE ZONE

“Fortunately”, the Belarusian Exclusion Zone is neither the sole nor most important place where we can find traces of the radioactive past. There was a much larger area that suffered from contamination, but could not be resettled or closed, and the people who lived there had to learn to live with an invisible treat. More than a million people, nearly 10% of the population of Belarus, live in contaminated areas. Furthermore, in many areas the evacuation was voluntary: residents were allowed to stay, but new ones could not settle there. As a result, today many areas are inhabited exclusively by old people. They are the Belarusian samosely (self-settlers).

Samosely

Samosely

In a situation where such a large population remains in areas affected by a disaster, it becomes necessary to create institutions responsible for monitoring the contamination levels of arable land, crops, livestock and food. Many production plants have specialized laboratories which test the supplied semi-finished products. It is difficult to evaluate the efficacy of these activities after several visits, especially since there recently was talk of a case where it was found that the level of radioactive strontium in milk was ten times over the limit. One thing is certain, however: we thought the regional products were very tasty. However, in order to raise awareness and sensitize society to the dangers of consuming contaminated products, special interest groups have been organized in schools to teach children how to check the level of contamination in their food using a spectrometer.

Laboratory at the Institute of Radiobiology

At school – special interest group that teaches children to check food contamination levels using a spectrometer

In addition to inspecting food products, it has also become necessary to establish medical institutions that provide the appropriate diagnoses and treatment for the exposed population. The Republican Centre for Radiation Medicine and Human Ecology was built for this purpose and is the largest and most modern hospital in Belarus, providing specialized medical care for people affected by the Chernobyl disaster. I have the amazing opportunity to visit the center and get an up-close look at the work of the Belarusian doctors.

Thyroid examination

Thyroid biopsy

Operation to remove the thyroid gland

THIS IS NOT THE END

It was an incredibly interesting and informative trip. I was not only able to see the most visible traces of the catastrophe – the abandoned homes and property of those who were evacuated – but also how difficult, long and painful the fight against radioactive contamination is. Material destruction, even on a large scale, sooner or later will be rebuilt. The health effects are much more difficult. The extraordinary dedication of the doctors and the sight of the suffering of the patients, particularly children, struggling with the effects of diseases resulting from events 30 years ago only show the true scale of the tragedy and how much still remains to be done. Ukraine was fortunate in its misfortune – the nuclear power plant was located in its territory and it receives funding for rebuilding from around the world. Belarus must cope with this alone.

********

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I would like to thank Mr. Vladimir Makei, Minister of Foreign Affairs of the Republic of Belarus, Mr. Aleksandr Titokov, Head of the Department for the Liquidation of the Consequences of the Chernobyl Disaster at the Ministry for Emergency Situations, the management team of Zapovednik, my colleague Phil Grossman, and all of the local officials for their help in organizing this visit.

I would also like to thank the two men in the white jeep who accompanied us on every step of our stay in Belarus.

Above all, I would like to thank the residents of Gomel, Khoyniki and Brahin for their incredible hospitality during all of my visits. It is to them that I dedicate this reportage.

Thanks for all of your Documentations. It is a really important work.

When you think about it, nuclear destruction is quite close to capitalism collapse… In Detroit, we can see the same desolation.

Great photographs by the way.